More mergers to come under scrutiny in another leg of Chalmers’ competition policy

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has unveiled new rules governing company mergers that will bring more of them under scrutiny to ensure they don’t worsen competition.

Chalmers says the changes – to be formally announced on Wednesday in a speech released ahead of time – are the most substantial in nearly half a century.

A mandatory notification system will be brought in and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission will be the single decision-maker on all mergers.

At the moment, notifications are voluntary, with the ACCC having the right to object after they have gone ahead.

Mergers above a yet-to-be-determined threshold and mergers which could significantly change market concentration will have to be notified and approved before going ahead.

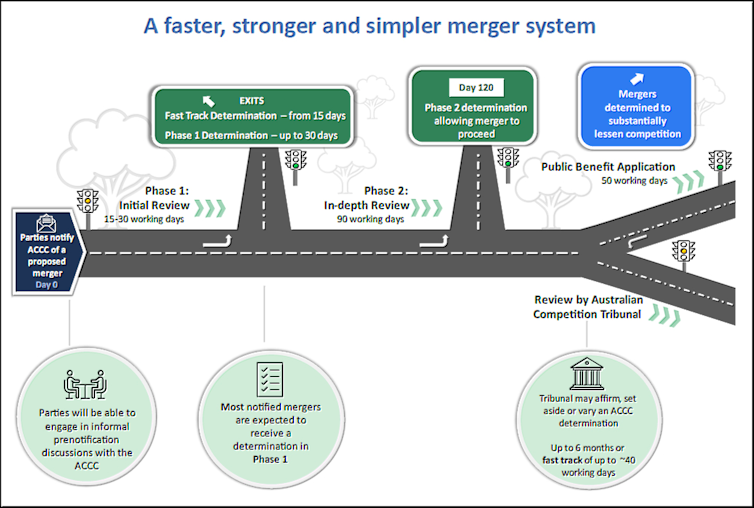

Under the new plan, which will apply from January 1 2026, mergers will be approved within 30 working days unless the ACCC raises concerns.

Firms will also have the option of “fast track” ruling within 15 working days.

Fees for service and a public register

Chalmers says the new system will be simpler, because there will be a single, streamlined path to approval, removing duplication and standardising notification requirements.

“It will be more targeted, because mergers that create, strengthen or entrench substantial market power will be identified and stopped while those consistent with our national economic interest will be fast tracked,” the Treasurer says.

For the first time, firms wanting to merge will be charged cost recovery fees, scaled to reflect the complexity and risk of the merger. The Treasury expects them to be in the range of $50,000 to $100,000, with additional fees for a review by the Competition Tribunal. The fees will not apply to small businesses.

All mergers considered by the ACCC will be listed on a public register, with brief information including the names of the merger parties, a short description of the transaction and affected products and/or services, and the review timeline.

Merger parties will be able to engage in confidential pre-notification discussions as to the information to be provided to the ACCC but will no longer be able to receive an “informal view” ahead of formally applying.

The ACCC looked at an average of 330 mergers annually over the past decade – only about a quarter of the total. Chalmers expected the workload to remain at about 330, but said it was more likely to be “the right 330” those with the greatest potential to cause harm.

The Treasurer hasn’t gone as far as the Competition and Consumer Commission wanted. The ACCC wanted merger parties to have to satisfy it that a merger was not likely to substantially lessen competition in order to get approval.

Several firms objected that this “reversed the onus of proof”, effectively introducing a presumptive ban on mergers.

The changes are part of the Albanese government’s general shakeup of competition rules which also includes a review of the food and grocery code governing supermarkets undertaken by former government minister Craig Emerson and proposals to loosen “non-compete” clauses governing workers who change jobs.

“Australia’s competitiveness has been declining since the 2000s,” Chalmerssays. “We see this in increasing market concentration.”

“Australia is one of only three OECD countries that doesn’t require compulsory notification of mergers.”

The Treasurer is also appointing merger specialist Philip Williams to the ACCC and updating the ACCC’s statement of expectations.

Williams is a former Professor of Law and Economics at the University of Melbourne.