We found out when the Nullarbor Plain dried out, splitting Australia’s ecosystems in half

Australia’s western and eastern ecosystems are biodiversity hotspots, separated by a dry desert interior. Yet millions of years ago, many species roamed more freely between connected habitats across the continent.

Our new research, published in Geophysical Research Letters, provides insights into ancient climate change that shaped our modern landscapes and ecosystems.

We have developed a new way to reconstruct the timing of great drying episodes on the continents of our planet. This work helps to gain knowledge about drylands that are particularly impacted by current climatic stresses.

Billions of people live in drylands

Drylands cover almost half of Earth’s land surface and are home to around 3 billion people. Dramatic, record-breaking droughts are increasingly occurring around the globe.

As the driest inhabited continent, Australia (70% is considered arid or semi-arid) also faces many challenges, including droughts and bushfires. Understanding the history of dry regions and their response to past climate change is important to mitigate the impact of our warming planet’s future.

Southern Australia’s Nullarbor Plain covers an area about the size of Great Britain (roughly 200,000 square kilometres). However, it is starkly different in almost every other aspect: extremely flat, very little rain, and almost no trees. These conditions and its size make the Nullarbor Plain a natural “biogeographic barrier”, separating rich and diverse ecosystems in west and east Australia.

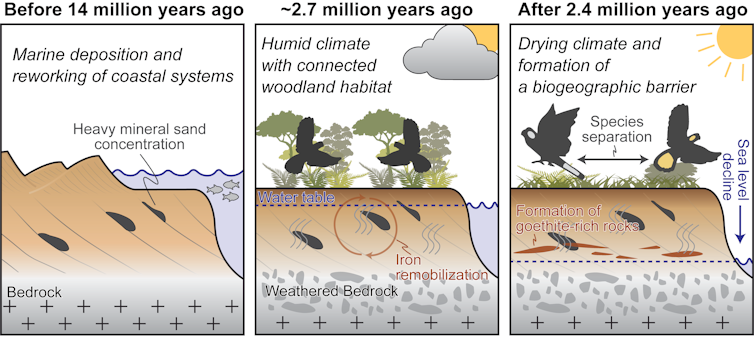

Today, the dusty Nullarbor Plain bears little resemblance to its vibrant past. Before roughly 14 million years ago it was covered by ocean and host to reefs. More recently, it would have been a lush home to an exotic menagerie, including the world’s biggest cuckoos.

Read more: The world’s biggest cuckoos once roamed the Nullarbor Plain

The drying of the Nullarbor

We know Earth is constantly evolving, but often have a poor idea of exactly when environmental changes occurred in the distant past. Fortunately, some minerals that record past climatic events can be dated.

For most people, rust is something they want to avoid, as it damages our cars, fences, and steel appliances. But rust can be useful in understanding climate change. In our work, we used an iron-bearing mineral called goethite – the main part of rust – to unlock the timing of drying on the Nullarbor.

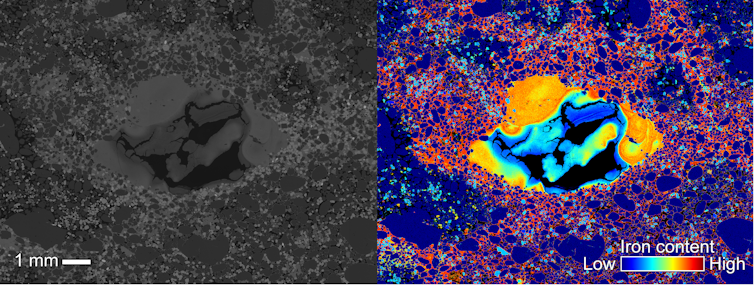

We found goethite in rocks some 25 metres below the Nullarbor Plain. These rocks mark the past level of groundwater. By dating the age of the goethite minerals, we can understand how past groundwater levels shifted in response to climate change.

We fired a laser beam into tiny pieces of goethite, roughly the size of a grain of salt, to release their atomic building blocks. We then measured the helium isotopes – variants of helium – that had accumulated since mineral formation. This provided us with a type of “clock”.

We calculated groundwater drastically declined on the Nullarbor Plain between 2.4 and 2.7 million years ago – at the same time as a period of global cooling.

As the climate shifted, the drying changed the local ecosystems, effectively creating a wall for many species. As large swathes of Australia changed from forest to dry grassland, habitat and food availability shrunk for many species.

Significantly, this barrier cut the once continuous link between the species of southwest and southeast Australia.

Splitting of the species

The evolution of many familiar species was influenced by this separation. There is the yellow-tailed black cockatoo from southeast Australia with yellow cheeks, and Carnaby’s black cockatoo with white cheeks in the southwest. Genetically, these two cockatoos are close relatives, but today live thousands of kilometres apart.

Through isolation, the drying of the Nullarbor played a key role in creating the species richness of southwest Australia. This region is one of only 35 biodiversity hotspots on Earth and home to more than 6,000 native species, with many found nowhere else.

Measuring the timescales of drying landscapes is important for conservation biology. Many native species are already facing or will face existential problems due to climate change and habitat degradation – including the iconic Carnaby’s cockatoo.

A history locked in minerals

By studying minerals formed during groundwater decline, we improve our understanding of our continent’s past and its biosphere. These minerals form as a direct result of continental drying, often in sediment with fossils of interest.

Previously, we often relied on indirect information like the chemistry of marine sediments to date continental landscape processes.

More broadly, having information on the timing of past drying events could help test theories about human evolution too. Changing landscapes and extreme drying were likely important for our own species development.

Determining the timing of environmental change lets scientists see how these events have impacted biodiversity and species evolution over time. Studying the past is also vital to understand how Earth responds to climate change. If we understand how ecosystems dry out, we can develop strategies to limit the damage.