We’ve designed a safe ‘virtual’ epidemic. Spreading it is going to help us learn about COVID

One of the biggest challenges in managing the coronavirus pandemic has been a lack of real-time information about the virus’s spread.

While the goal of well-intentioned governments is clear — to mitigate spread with minimal economic and social impact — it is very difficult to decide on the best policy to achieve this.

In Australia, public health authorities have been consistent in encouraging testing for the virus. The major driver behind this has been the desire to find positive cases and track their contacts.

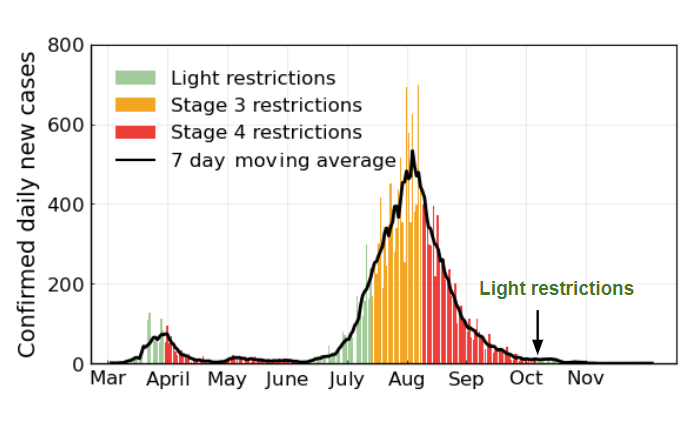

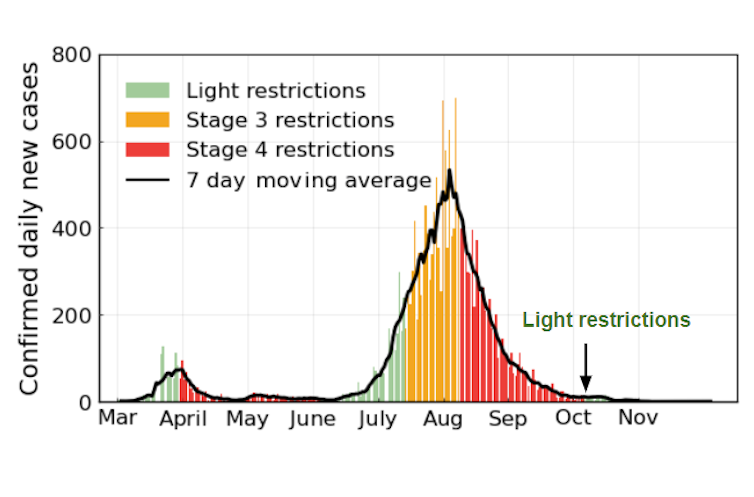

A by-product is information about how the virus is spreading in the general population, which can be used to inform decisions about measures such as mask-wearing and restrictions on movement.

However, at best, the information provided by testing individuals is partial, biased and delayed. This makes it hard to make real-time decisions about when to impose restrictions, which are arguably the most important tool in the fight against the pandemic.

To help out, we devised the Safe Blues framework. This is a joint project between researchers from The University of Queensland, The University of Auckland, The University of Melbourne, Cornell University, Columbia University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Macquarie University and Delft University of Technology.

In this framework, virus-like tokens are spread between mobile devices via Bluetooth, similarly to how a biological virus spreads between people.

If adopted, a tool like Safe Blues could help public health authorities better control outbreaks by providing data on the general level of contact between people. Our paper published today in the Cell Press journal Patterns summarises the idea.

Read more: How to flatten the curve of coronavirus, a mathematician explains

What about COVIDSafe?

Last year the Australian government released the COVIDSafe contact-tracing app. It was backed by an extensive government-funded media campaign and initially adopted by millions of users.

COVIDSafe works by using Bluetooth signals to record digital “handshakes” between the smartphone of a user and nearby contacts who also have the app. It stores this information in a form that can be retrospectively accessed if the device’s owner tests positive. Their contacts can then be traced and tested.

While the idea has merit, there have only been a handful of instances where the app was able to pick up confirmed cases more effectively than human contact tracers. So is the marriage between Bluetooth and public health useless?

We don’t think so.

Spreading a Bluetooth-powered virtual virus

Social distancing works on all viruses, not just SARs-CoV-2 (the virus of the COVID-19 pandemic). For example, major COVID-19 lockdowns not only curbed the spread of SARS-CoV-2, but also mitigated the spread of the common cold.

With this in mind, let’s return to the lack of information problem and consider a thought experiment: what if we could create a virtual virus that spreads exactly the same as COVID-19? Although this one would be harmless and traceable in real time.

By studying how this virtual virus evolves, we would be gleaning important insight into how SARs-CoV-2 evolves. This could empower decision makers to devise the best strategies to enforce restrictions and prevent the virus from spreading further.

To implement the framework, the mobile devices of a random subset of the population would be purposefully infected with the safe digital virus, which we call Safe Blues.

Then, based on the measurements of how this “infection” spreads, public health authorities could get a better picture of how the real coronavirus spreads.

Statistically, the number of cases and patterns presented on the Safe Blue app would follow similar trends to the real virus.

Of course, the actual individuals infected with SARs-CoV-2 and those infected with Safe Blues would not be the same. In fact, simulations have shown only a small fraction of the population would need to participate with a Safe Blues app for it to deliver reliable predictions.

It’s important to note Bluetooth signals don’t propagate like viruses. But if we generated hundreds of variants of Bluetooth-based virtual tokens, this ensemble could capture many of the social movement patterns that drive infection — and thus could be correlated with the real virus.

Where to now with Safe Blues?

Safe Blues’s machine learning methods have been developed and evaluated using mathematical simulation models. Initial results show that an ensemble of Safe Blues token strands can yield powerful estimates of actual epidemic behaviour.

The Safe Blues team is now working towards a system pilot at The University of Auckland. Using an experimental Safe Blues Android app, the aim is to generate and study how the virtual virus spreads in a campus setting.

The insights provided by the app could also be coupled with data from waste water measurements and from existing social networks such as Google, Apple or Facebook.

We believe virtual virus spread techniques such as Safe Blues could greatly contribute to our real-time understanding of this pandemic, as well as future epidemics.